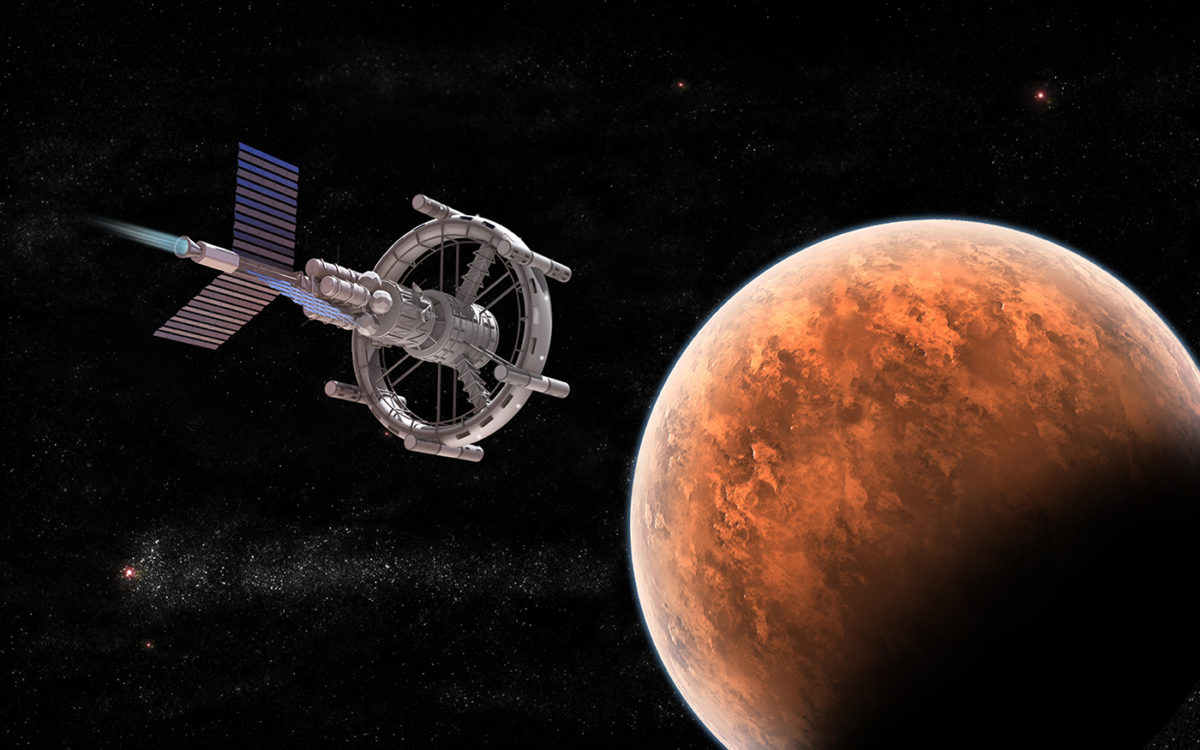

(a+b): Space Design, an exercise in imagining future scenarios

This article was written for Salone del Mobile.Milano and previously published on salonemilano.it digital platform

Both PhDs, architects, designers and lecturers at the Polytechnic University of Milan Design School, Annalisa Dominoni and Benedetto Quaquaro are the founders of the (a+b) studio and the leading experts in architecture and design for space and extreme environments. They regularly collaborate with leading international space agencies and industries and with prominent design companies. They also carry out research at the Polytechnic University of Milan Design Department, in addition to teaching and publishing essays on design culture that have helped affirm the strategic role of design in space.

c

Annalisa Dominoni and Benedetto Quaquaro, A+B photo courtesy

Space Design: what does designing for space mean and what does it involve?

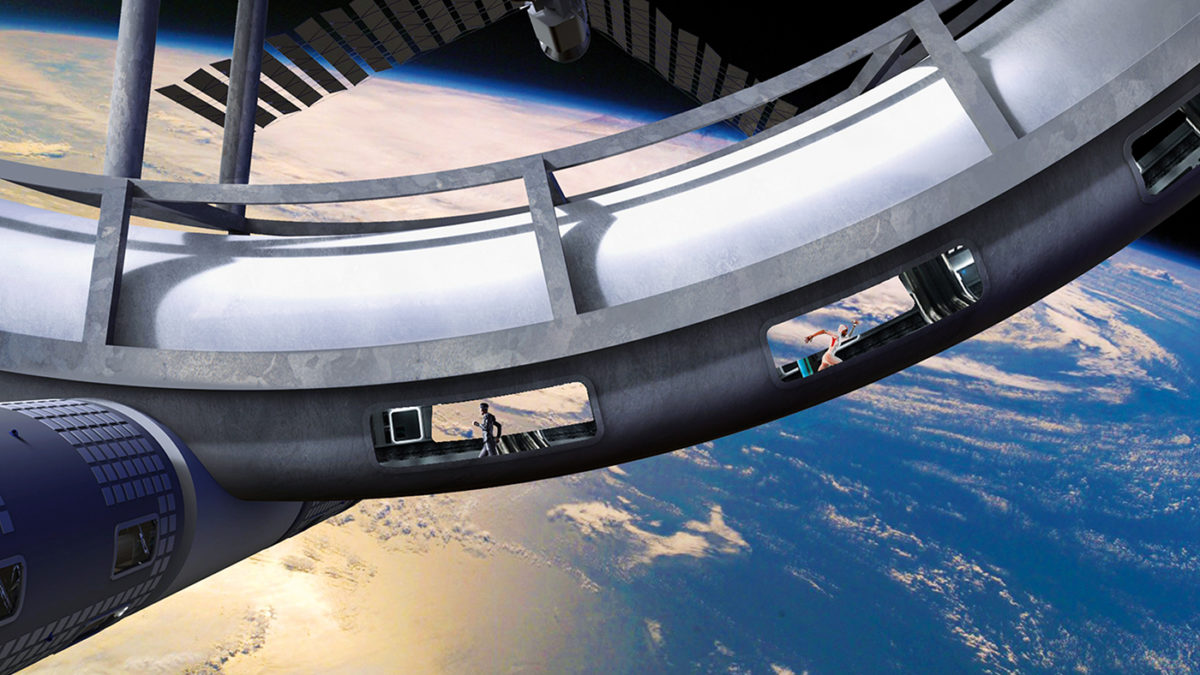

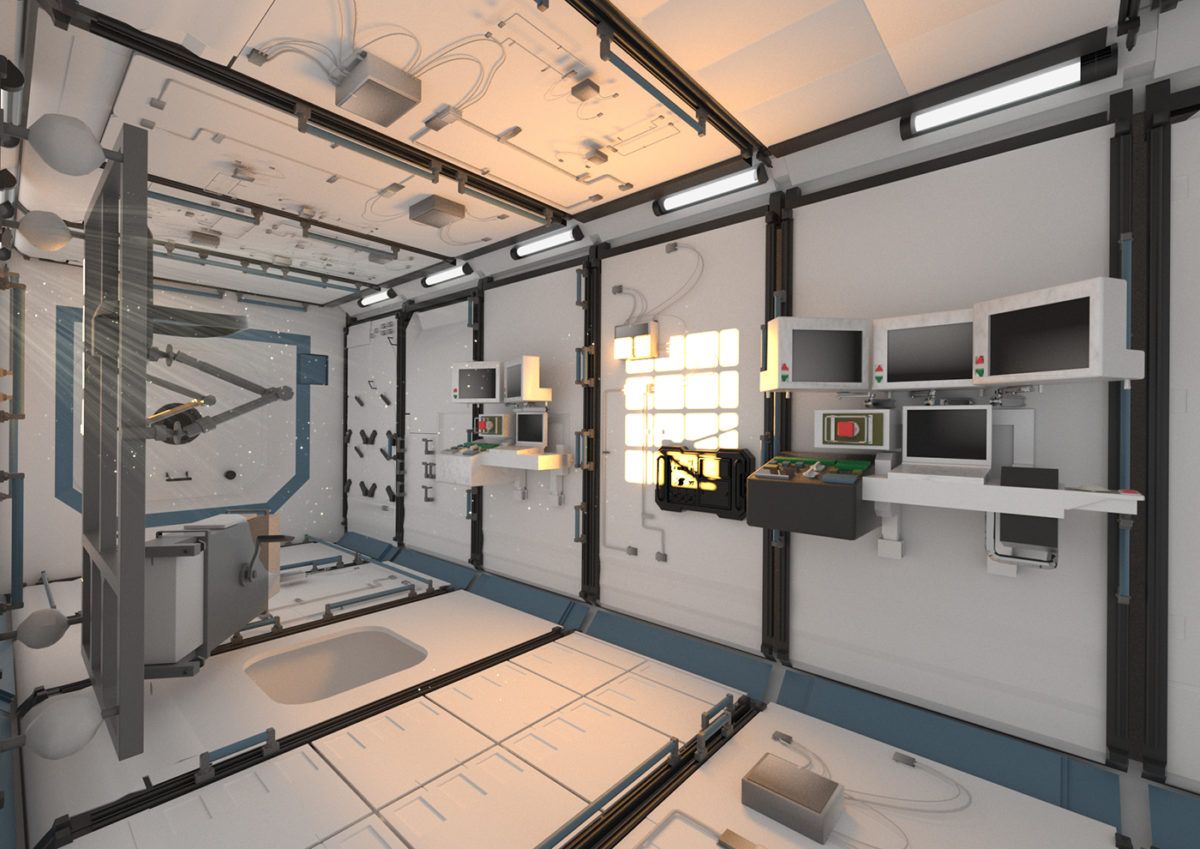

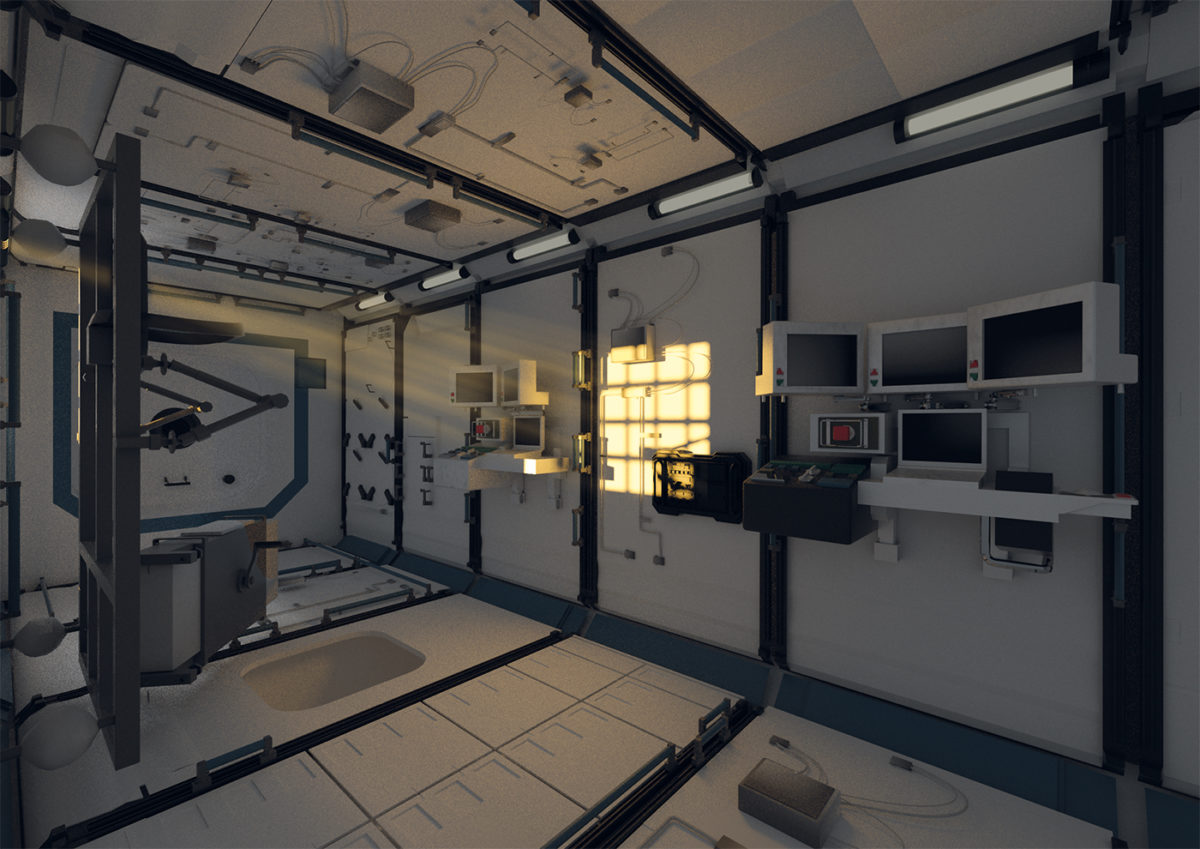

Space design means “starting again from scratch,” adopting a different mindset and thinking about somewhere completely different, applying new methodologies to the projects, envisioning habitats, equipment and instruments for uses and activities that those of us who live on the Earth can hardly imagine but which, in most cases, involve a different relationship between our body, the objects and the surrounding space. Living in space involves two particular conditions: confinement, which can also be tested on earth, and microgravity, which is not part of our day-to-day experience and which demands a huge amount of foresight in trying to imagine how an object will behave in space, how it will be used and how it will relate to the surrounding area, given that the lack of gravity alters many physical and cognitive, physiological and postural, ergonomic and motor parameters, as well as psychological and emotional, of which we have no experience. This is an extremely difficult endeavour, in that the infrequency of human space missions have made it hard to create an established and, especially, codifiable experience in terms of the effects and the behaviours of human beings in space.

Our main aim is to demonstrate the centrality and the progressive diffusion of space design, which is taking on a strategic role within a scientific community, through projects, research and participation in events, symposiums and publications. Design is distinguished by the powerful creative ability to generate possible new future scenarios, putting the needs of human beings at the centre, and giving “shape” to extra-terrestrial habitats and new products through projects that amalgamate different languages, including that of science and of technology, but also of usability and beauty. In our architectural space products, we like to look beyond the functional aspects and consider the physiological and emotional ones, which have a huge influence on our behaviours and on our wellbeing.

Aside from designing sensorial environments, we believe that space design should inspire private as well as design companies, with groundbreaking ideas capable of triggering new visions, new applications for space technologies, as well as good practices and behaviours, that can be transferred from space to earth and vice versa. We think about new ways of inhabiting space, and technological applications and terrestrial behaviours that could inspire new projects for improving the lives of astronauts. In the age of the New Space Economy, designers also become “producers” of ideas and suggestions, “connectors” between futuristic scenarios and technological development, creating a dialogue between very different production skills that will generate innovation.

c

Space4InspirAction with Technogym. 4th edition 2020, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

On the subject of design brands, what has their reaction been? What are the challenges and the lessons?

As well as collaborating with Thales Alenia Space, it’s really important for us to involve design companies and space companies every year, which have the specific know how for tackling the various projects.

Their initial reaction is one of enthusiasm, along with a slight, totally legitimate, fear of not being up to taking on a field like space, which is recognised as being the most technologically advanced, and not having the necessary tools with which to do so. This is where we come in – our job is to speak different languages and to act as a “bridge” between space and Earth, bringing science, technology and beauty together, demonstrating the extremely important and strategic role design can play in generating innovation inspired by space technologies, as well as good practices and behaviours that can be an example to those of us who live on Earth – and vice versa.

While working on our projects we have happened, during the latest space station concept commissioned by Thales Alenia Space for instance, to propose the use of Caimi Brevetti’s acoustic textiles for lining the interior of a particular habitation module devoted to entertainment, for which we were very particular about the sensorial and sensitive aspects such as sound absorption, light quality, colours, the materials that would make the entire space much “softer” and more welcoming. NASA is testing Caimi Brevetti’s acoustic materials at the moment, to see if they could be integrated into the International Space Station (ISS), which is an extremely noisy environment. We think this marks a great success for a design company and we’re really glad to have been able to create that “bridge” and that the company has taken on the challenge.

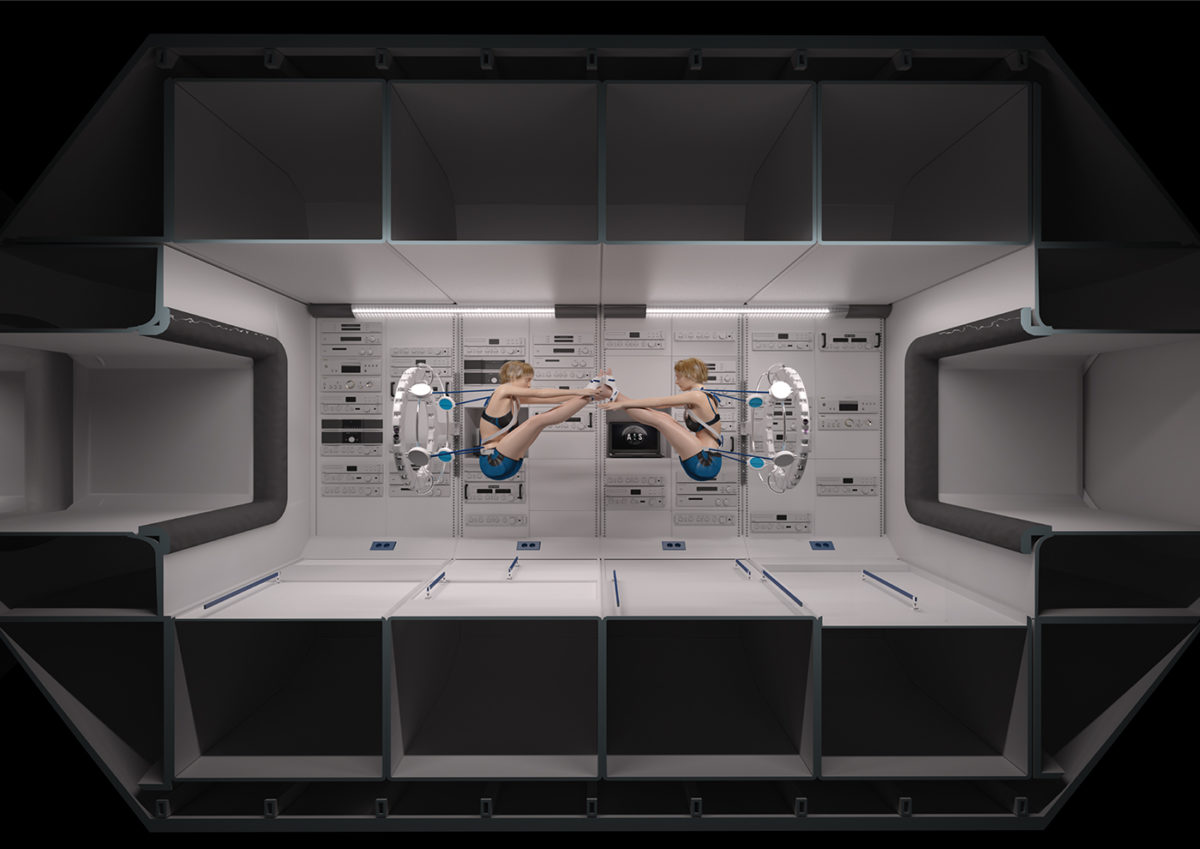

This has given rise to many more. We explored the issues involved with food in space with Argotec, from both a nutritional and a technological point of view, keeping gestures very much in mind as always, and came up with new 3-D printed pasta shapes and new ways of enjoying wine without it escaping from the glass, with Barilla, Ancap and Italesse. We brought in TechnoGym, in a bid to make the astronauts’ physical activities more pleasant and enjoyable, and also introducing paired and group exercises, to reinforce the crew’s sense of belonging. In one of the 12 projects we carried out, the inspiration of the movement of the acrobats was a useful spin-in for thinking up new ways of exercising on board. We have designed new interior spaces with Foscarini, harnessing light to recreate terrestrial “landscapes” like the Japanese komorebi: it’s the dappled light that filters through leaves on trees, it’s a state of mind, an atmosphere that we have tried to reproduce artificially, with an eye also to re-establishing the circadian rhythms, which are affected by the lack of natural light in confined environments.

The challenges we take on with our companies are always very exciting, because we push them beyond the established models, to create new things. We believe that space will have a defining influence on our lifestyles not just now, but increasingly in the future, improving performance quality, altering behaviours and creating new needs … the first design companies to embrace these new opportunities and translate them into products will be the pioneers of the near future, which is already here, even though not everyone’s realised it yet.

c

Space4InspirAction with Barilla, Ancap and Italesse. 5th edition 2021, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

What can this discipline teach students and designers in 2022?

Space Design is a very powerful way of freeing ourselves of the mind maps and plans built up over the years that constrict our imaginations and of opening ourselves up to new things, to the unknown. The students who enrol in the Space4InspirAction course – the first and only course in architecture and space design in the world recognised and supported by the European Space Agency (ESA) that we teach at the Polytechnic University of Milan – are particularly attracted by the opportunity to experiment with life in other worlds, to imagine scenarios that are not part of their terrestrial experience, increasing their capacity for envisioning and, especially, for designing spaces, furnishings, equipment and objects alongside experts, scientists from ESA and the companies that help us give shape to these new scenarios.

The same exercise is true of the designers whose approach is to crosscut industrial research and know how, understanding how to design for the purpose of increasing wellbeing and sustainability, who are attracted by scientific and technological innovation and look to the future with confidence, endeavouring to come up with solutions that will allow people to live in space as we do on the Earth right now, but with greater awareness of and respect for our planet and its resources.

c

How did your collaboration with the space agencies come about?

Looking up at the stars … and wondering what an architect and a designer could do space-wise.

c

There’s also a specific methodology for tackling these projects, Use and Gesture Design, what does it entail?

When we design for astronauts, we try to immerse ourselves in the ambiance of the International Space Station (ISS) and imagine how our bodies might move in microgravity, how our posture and our gestures might change in relation to the objects and, especially, how the new tools for functioning well in space too could be designed, and, why not, leveraging the lack of gravity, which has always been seen as a barrier to be broken. Our experience in design and research at the Polytechnic University of Milan Design Department has allowed us to hone a new methodology that we have called Use and Gesture Design (UGD), which is based on the simultaneous design of spaces, objects and gestures. In other words, in tandem with developing the project, we also conduct a careful analysis of the actions, movements and gestures of the body in microgravity. In the design process, the “artefact” is just as important as the “patterns of use” and the creation of an idea, a design concept for space stems from the simultaneous design of simulated actions, movements and gestures based on how the design object should or could be used, how and with what procedures, how long for and by how many “actors.” To cite Pierre Rabardel, it’s as if the formal and performance-based idea of a project was being developed contemporaneously with a potential “screenplay” of the movements and gestures of the actor.

If designing for space means projecting the global characteristics of the future object onto the scene of its possible uses and visualising it in action in our hands, or being worn in the microgravitational environment in which it will be used, it therefore follows that, at the end of the day, the actor is the author of the object, because his actions make it complete and fully actualised. Every time it is used should be considered an interpretative action and, while developing the products, designers valorise both the gestuality and the movement that accompany the object, and the object itself, seeing themselves, as in dance, as the inventor of the gestural programme, of the ritual, and not of the traces it leaves.

c

Space4InspirAction with Foscarini. 4th edition 2020, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

Space4InspirAction with Foscarini. 4th edition 2020, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

1. Space4InspirAction, 1st edition 2017, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano

Space4InspirAction, 2nd edition 2018. Ph. Credit Annalisa Dominoni, Benedetto Quaquaro

Cover, Space4InspirAction, Scuola del Design, Politecnico di Milano