#INTERVIEW: “DESIGN. UNA STORIA SBAGLIATA” by Maurizio Corrado

Architect, essayist, writer, Maurizio has been involved in the ecology of the project since the nineties, carrying out educational activities and organizing cultural events, he also curated design programs for Canale 5 and SKY. He has published with several publishers (De Vecchi, Electa, Edicom, Xenia, Macroedizioni, Esselibri Simone, Wolters Kluwer, among others) over 20 books about design and ecological architecture, some of which translated in French and Spanish. He directed the Italian/English magazine Nemeton Magazine, the series Costruire Naturalmente for Esselibri Simone, Progetto e Natura for Wolters Kluver, Fare Paesaggi per Compositori, Audioarchitettura for Area51. He is a lecturer at University of Camerino, Naba in Milan and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and Verona. He writes a blog on Repubblica: “L’Architetto nella foresta.” He is considered one of the leading Italian experts on the relationship between plants, architecture and design. He writes literature and theater.

v

– “Design. Una storia sbagliata” (Design. A wrong story), is not the usual design text, but almost a journalistic investigation that shows us another point of view on design. Why did you feel the need for this “counter-history of design?

I have been participating in design since the early eighties, as designer, journalist, essayist, teacher, event and exhibition organizer, as if to say I have been in every part of the design system. From the mid-nineties I began to deepen the culture of the ecological project. In my opinion, thanks to this, I could clearly see how all the problems reported by the first ecological culture were a consequence of the industrial system; design is one of the sub-world of this system. A part of the disease. However, excluding some rare thinkers, for example the protagonists of the radical architecture, the disciplinary debate takes place on completely different themes, or rather, takes the industrial system for granted, while I clearly see how the problem is exactly there. Adding this to the fact that, for some years now, reading habits have changed radically, I saw that a fast, short, documented text, able to consider all the chronological span of industrial design until today, was missing. In fact, it is a militant text. A friend, after reading it, told me: “Taken away the crap, it’s what it’s needed.

v

– The text is ironic, sometimes sarcastic, it deals with the topic in depth, but with a smile. Why this stylistic choice?

As a journalist, I grew up inside Vogue magazines and there I learned that if you mean the worst things, if you say them with a certain brilliance, they are likely to arrive. It is a technique much more difficult to control than usual essays, but which has the great advantage to revealing the real life of things and of those who make them.

v

– For each chapter there is always a chronological connection with the culture and history, contextualizing entrepreneurial choices and products, production processes and styles. How come today’s design seems to be totally taken out of context? Why does “the good intentions of the sector, or those of improving the life of man in a brilliant and minimally invasive way, were soon lost on the street”?

The problem is not in the design, but in the lifestyles that it proposes, or it would be better to say, the lifestyles that the industrial system imposes. Ivan Illich used to say: “Freedom is no longer desirable.” When you are no longer a man but a consumer and you are proud of it, the only need is to have money in order to buy and who has more money is your model. Everything around you serves a specific logic: buy, consume, throw, in an endless loop. Part of contemporary design serves this logic, there is no space for anything else. If you’re in it, good, otherwise you have to struggle a lot, and not just as a designer.

v

– “Let’s start imagining” is the proposal to correct this wrong story, a hope and a method for the future. Simply? Designers would have to start imagining again, but how should the design brands and the market behave?

The re-appropriation of the capacity, the possibility and the power that imagination has, is a primary and unavoidable factor, especially today when this weapon – the only one in the hands of individuals – risks to atrophy for the overflowing archive of ready-made solutions available on the web. When we look for something, the habit to rely exclusively on Google, or similar, turns off the possibility that our brain has to create new solutions. We are addicted to finding ready-made solutions, without wondering who gives them to us and above all, why those and not others. In another work in collaboration with the anthropologist Matteo Meschiari, Paleodesign, there is a sentence: “To sit down you just need a stone, everything else is imaginary”. This is enough to understand what the designer’s work is. Companies must be the designer’s tool to spread culture, it is a very difficult task, I know, but otherwise what are we doing here? If someone wants to continue acting like the dog of the small factory owner, go ahead, he will certainly have an easier life, a warm kennel and bones to gnaw in abundance. As for the market, I have just read the research of an Indian economist, “The dawn of the Solar era” by Prem Shankar Jha, which shows how the market mechanisms are bringing our civilization to collapse. If I can say it: the market? Fuck it.

v

– Your path is very interesting, you were also the founders and one of the Bolidism theorists, what has changed since those years? What role does designers and companies play in that period?

Luckily, one of the things I saw and now I am seeing again, is the desire to discuss, talk, tell, invent. In the eighties there was a big empty bubble, which inflated the ego of the designer. The idea of the demiurge/god architect is always creeping in our practices, and this produced the idea of the archistar – I remember the term coined by the American mathematician Nikos Salìngaros had a negative sense which then became the opposite value. I know that for some years now some people had doubts, questions, there is a certain uneasiness among the newest generations. This leads us to doubt the role of the designer as a divine solver and to look around, question other disciplines, which for a designer is fundamental: not working in groups as it was done in the seventies and eighties, on the model of rock bands, but exploring every topic from many points of view, being interested in anthropology, history, natural sciences, genetics, music, paleobotany…

v

– What is the future of today’s young designers, thinking of students and professionals under 35?

There are many areas where the designer’s work would be really appreciated, for example medicine and everything that has to do with physical difficulties of any kind. In these fields professionals use old tools, they should be re-designed, there would be a lot to do. The project can help all those areas concerning human life, it could really help you to live better, beyond tables and little chairs. Moreover, today there is a problem that can no longer be postponed: the real danger of extinction we are running towards. A delicate subject that seems to be pointless, since the seventies the scientific community has been launching appeals that unfortunately are coming together. Saying “There are ten years to collapse” is now a mantra, that like any other serves only to sleep without listening to its meaning. I would have a look, maybe to recover the ability of the hand, to re-evaluate the gesture, to discover the possibilities that all the primary materials have, to study them and to learn how to use them, without waiting for the already processed materials supplied by the industry, it could turn out to be literally of vital importance.

v

– What role does design teaching play today? What has to be kept and what has to be changed?

What I see is a great job to create technicians who think little and work a lot. Everyone is good at doing projects, impeccable renderings, but without any kind of question. In essence, we create people able to do things without wondering what are they doing, because it’s taken for granted that the market will tell you. It is good to train people to do projects, but it is better to give them tools to understand what to design, methods to interpret reality. This is what a designer must do if he wants to intervene in our reality, it is always complex, the more you know, the more the project is effective. The designer must be a visionary, necessarily, he must have the vision of the future. I think that’s why the only literature that really inspired the designers was visionary and science fiction.

Thanks Maurizio for this interesting interview. You can find “Design. Una Storia sbagliata” on Amazon. Below the gallery you can find the image captions, small excerpts from the book.

v

Clothespin

Clip

Martini Glass

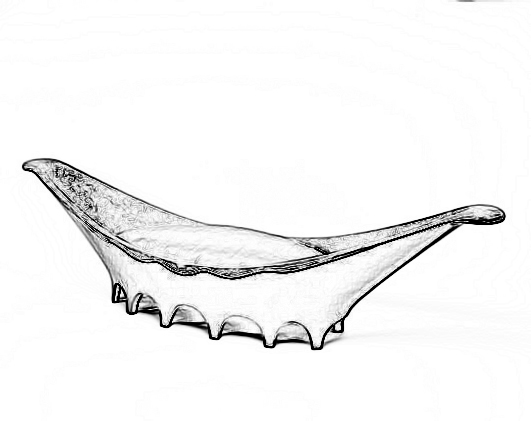

Pirogue

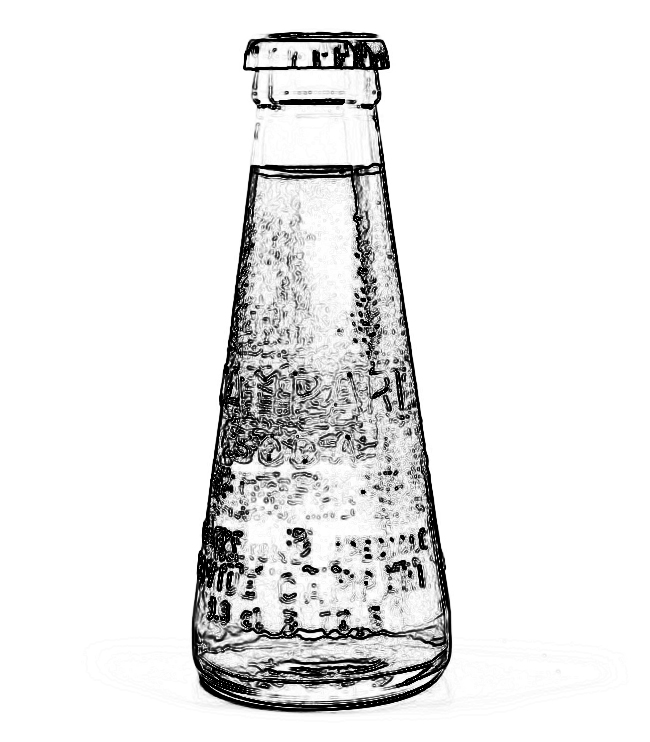

Campari Bottle

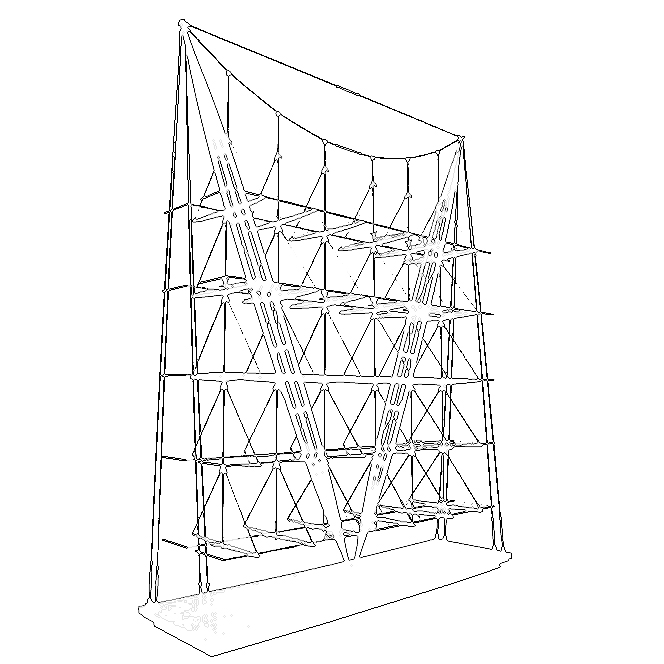

Veliero

Bowl Chair

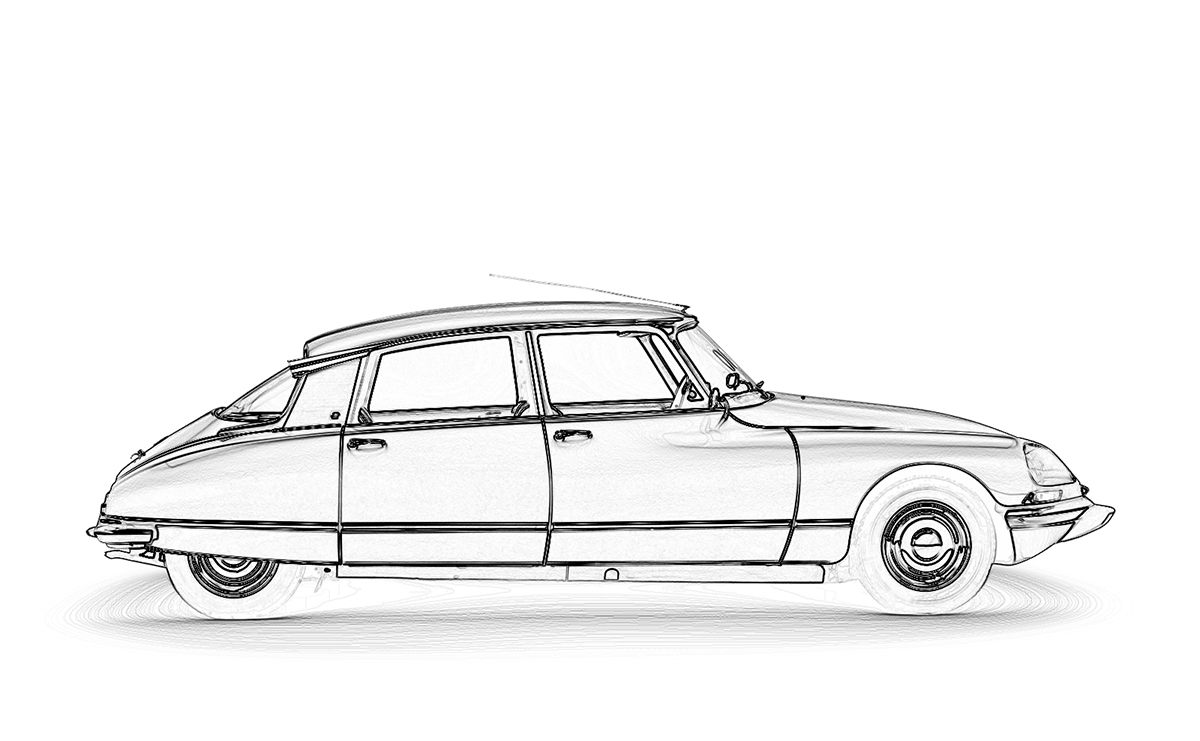

Citroen DS

Superstudio

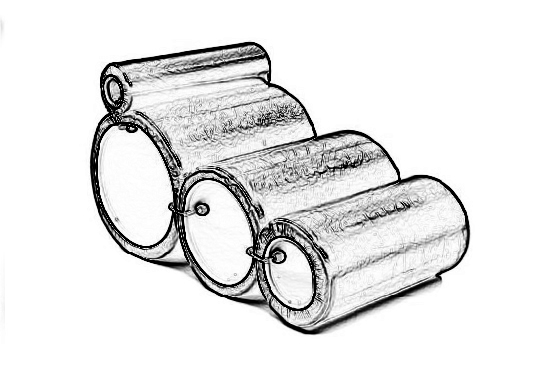

Tubo Chair

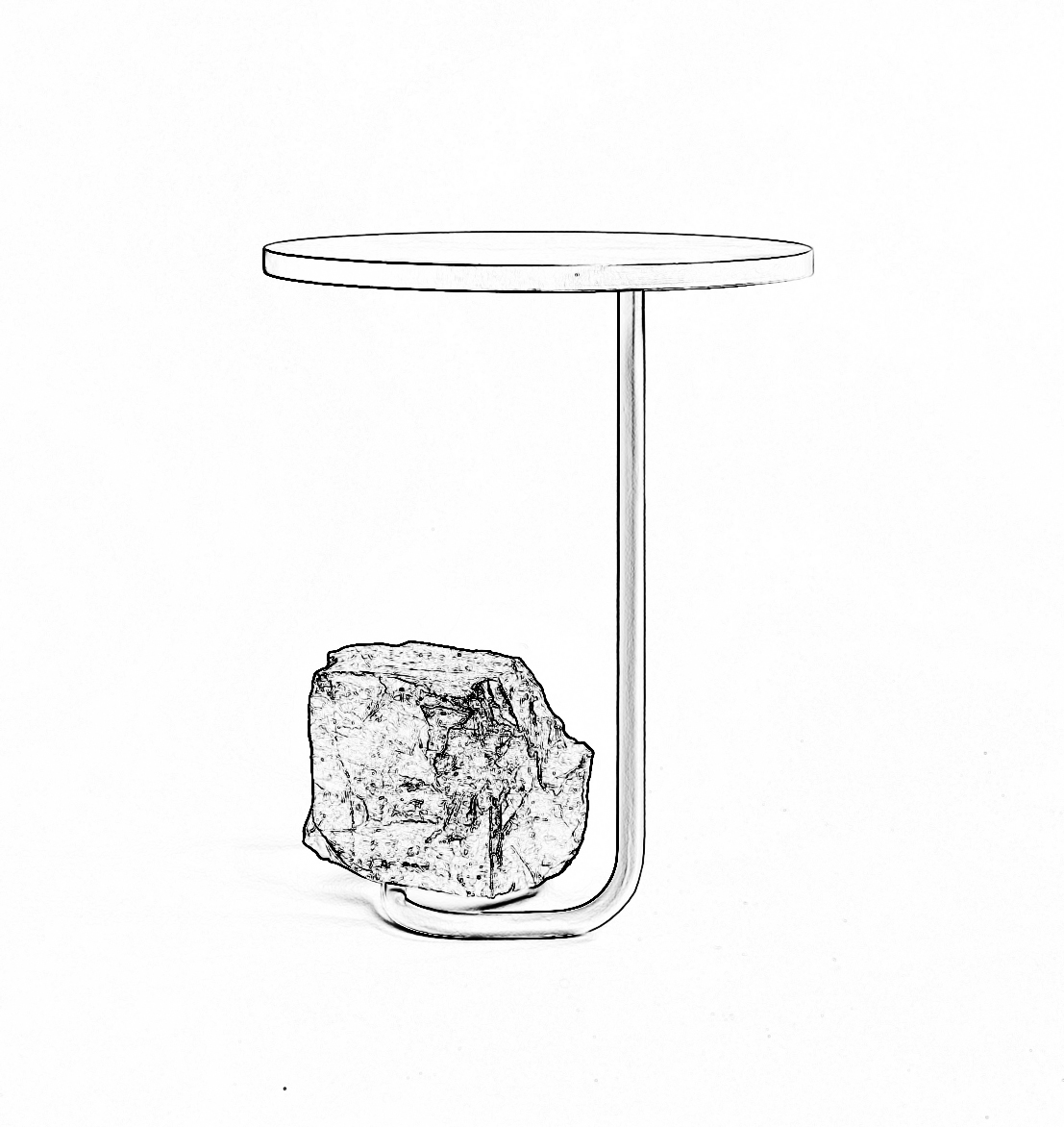

FurNature

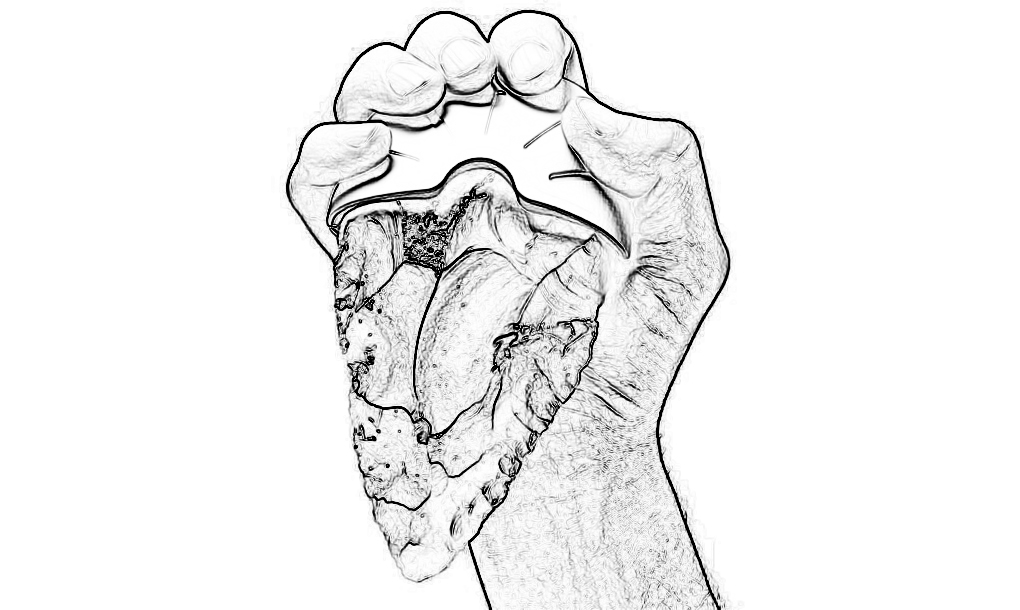

BC – AD

Clothespin –September 8, 1784. At 48, Ann Lee died in a small village in Albany County, in the United States. Ann thinks she is the female incarnation of Christ and is the head of a Puritan Calvinist religious sect, the United Society of Believers in the Second Apparition of Christ, otherwise known as the Shakers: when they imagine the Holy Spirit is coming, they stir in mystical ecstasies. Despite the radical landscape of the Puritans, the Shakers are extremists. They live in absolute celibacy and, terrified by the contagion of sin, things are built autonomously, an exercise that leads them to inventions like the first clothes clip, a piece of wood with a slit in the middle then perfected up to what we see, patented in 1853 by a certain Mr. Smith of Springfield, one of the 146 patents for clothespins granted between 1852 and 1887. Unbeknownst to them, the Shakers played a fundamental role in the development of industrial design. The young Adolf Loos meets them in 1892 and, struck by the purity of their furnishings, becomes the spokesman of the Shakers philosophy that sees decorum as a manifestation of Satan. The stench of this moral swamp permeates the Modern Movement from the beginning, it will never be able to free itself from the mephitic influence of Ann Lee.

Clip – 1867. The American Samuel B. Fay is the first to patent a paper clip which will then be perfected to become the one we know. This kind of objects constitutes one of the best sides of design, little things that help us every day, in silence and without pretense. When the history of design is intertwined with the one of inventions, these small silent miracles can be born. The second half of the nineteenth century is one of the periods in which patents abound, from the telephone to the elevator, from the refrigerator to the light bulb, the world is preparing for a change perhaps only comparable to the one occurred in the Neolithic.

Martini glass– We are in the 1920s. The war is over, forgotten the pain and guaranteed the fun. The swing goes crazy at full volume in the places where you dance; the electric light, just arrived, allows us to live the night; the metropolises sparkle, we toast to the new century; even the glasses are simplified, the champagne cup is geometricalized as it wants the fashion of the moment and an icon is born: the Martini Cup or Martini Glass, to welcome the coolest cocktail of the moment.

Pirogue – Between 1918 and 1922, Eileen Gray worked for Madame Mathieu-Lévy’s apartment in Paris and created Pirogue, an indefinable and magnificent living room furniture, unique, which would then be exhibited in Jean Desert’s gallery. Eileen Gray is one of the first designers of the twentieth century, an exceptional woman with an intense, scandalous and sparkling life, which is obviously good for health, since she didn’t want to know about leaving before 98 years of age. Bisexual declared in the Paris of the Twenties, friend of artists, painters, musicians and architects, she started to design furniture almost by accident, perhaps because what she found around didn’t satisfy her taste.

Campari Bottle – 1932. Davide Campari decides that it is time to launch the single-dose aperitif and entrusts Fortunato Depero with the design of the bottle. Since the mid-twenties Depero has used the conical shape for Campari, it appears in two puppets from 1925, in a sketch of the ’28 the bottle has a crown cap and appears later in other drawings. It is Davide Campari who does not want the label to bring out the red of the drink. Depero and his work is one of the examples of how art, communication and design often go hand in hand.

Veliero – 1938. Franco Albini designs his own library and conceives it as if it was a sailing ship. The plans will be in glass, nothing will be fixed, everything will be in tension, two uprights will pivot in one point and will be kept in tension between them by steel cables to which the plans will be hung. Pure tension.

Bowl Chair – 1951. Lina Bo, trained as an architect in Italy in the 1930s, deputy director of Domus, from 1946 in Brazil, where her unconventional soul emerges, is still a figure almost unexplored. Her Bowl Chair is a hemisphere that rests freely on a metal structure and it anticipates many of the subsequent chairs.

Citroen DS – October 6, 1955, one of the most beautiful cars in the world is born, the Citroen DS, déesse in French, Dea. Squalo, Nautilus, Iron from Ironing, Whale, Slipper, Bathtub, however it has been called, is one of the most admired cars in history, daughter of Flaminio Bertoni’s Italian pencil and the French farsightedness. If you have tried it, it is difficult to forget the moment when, sitting on its soft pillows, you turn it on. Starting from the long snout, the car, with a slowness of an embarrassing sensuality, rises, rises, merges into the sky. And what about the fluctuating movement resulting from one of the most innovative hydraulic suspension systems that keeps its lucky inhabitants in a state of sweet suspension?

Superstudio – We are in the mid-sixties. In the Italian Faculties of Architecture, for some years now, student movements have been questioning not only design and architecture, but the whole industrial, liberal and capitalist system. The revolution is boiling and seems inevitable. We produce ideas, objects, images, they are all visions, proposals, hopes, provocations, actions that anticipate the future. In this vision of Superstudio the space is empty, objects no longer exist or do not exist yet, bodies, actions remain, space is liberated, lightened, new.

Tubo Chair – 1969. Four plastic tubes that can be inserted one into the other, covered with polyurethane foam and finished with vinyl , plus a couple of metal elements that hold them in the positions you want. It is one of the obsessions of those years, the objects are at the service of those who use them, ductile, maneuverable, transformable, multi-functional, combinable at will. The Tubo Chair is one of the many projects developed by Joe Colombo in this direction. Legendary designer among designers, Joe is the most northern of Italian designers for the unconventional use of plastic and visionary ability.

FurNature – 2016. Furnature is a project by Sovrappensiero studio, objects that need the users to be complete, the project stops a moment before the presumption of completeness, as in times of revolution, we look for the space of man, of everyone’s fantasy. The table to “stand up” will need something I put, it becomes mine, and the anonymity of industrial seriality can fade and fade away.

BC – AD – The alliance between us and things is an ancient pact, difficult to change unilaterally as we have tried to do in recent times. Things do not rebel as in science fiction, they simply do not die, they do not disappear, they turn into zombie objects, they continue to live somewhere else until we see them returning, out of the garden in front of the house. Rethinking the alliance starting from the Pleistocene in us, rediscovering gestures and materials, as Ami Drach and Dov Ganchrow seem to perceive with BC – AD, a series of stone and latex objects from 2014.

All Rights reserved to Maurizio Corrado